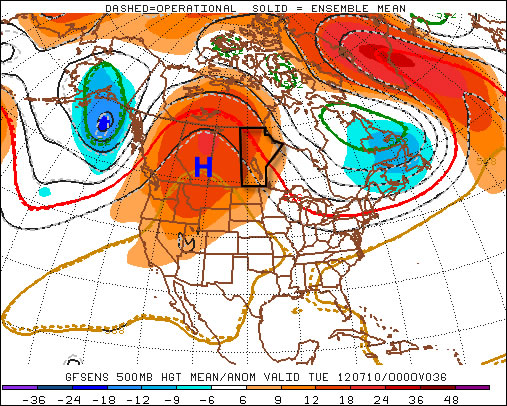

Winnipeg may see the warmest day of the year today as temperatures soar into the mid-30’s under the influence of an upper ridge and southwest wind. The upper ridge that has brought us our sunny weather will then be weakend by multiple upper disturbances tracking across the Prairies, bringing us a few days of more unsettled weather across Southern Manitoba.

A southwest wind, combined with significantly warmer temperatures under the upper ridge (around 22 or 23°C at 850mb) today will help Winnipeg’s temperature soar to a scorching 35°C if we can stick to sunny skies. Today will be the warmest day of the week, with temperatures returning to near 30°C for Thursday and Friday. Overnight lows will be mild with the temperature bottoming out at only around 19°C.

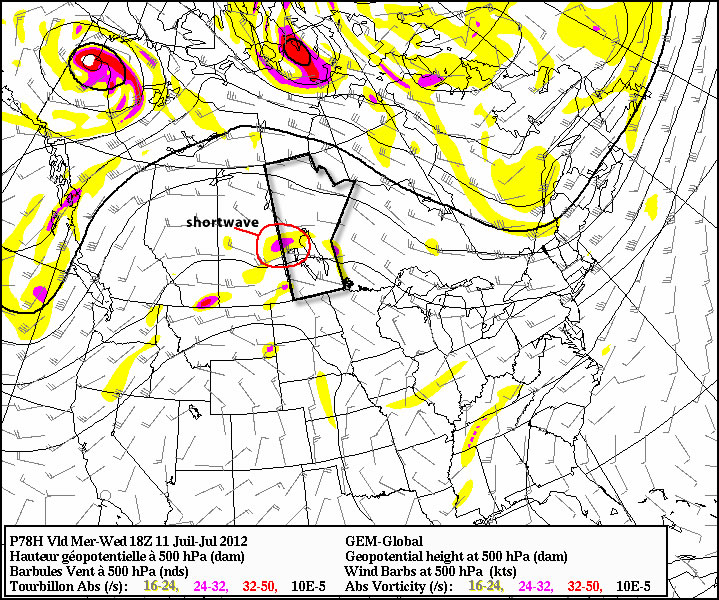

Several disturbances are set to track through the southern portion of the province beginning this afternoon/evening, which will bring us a risk of thunderstorms late this afternoon and this evening as well as tomorrow afternoon/evening. While some storm parameters will be significant given the heat, a distinct lack of wind shear will ensure that any storms that form will likely be relatively slow moving pulse-type storms. They may strengthen to severe levels, but they will likely be scattered and it will be quite hit and miss as to who sees them and who doesn’t. The main threat from the storms would be large hail and heavy rain. Strong winds area also a possibility. Extremely weak wind shear will likely preclude the development of tornadoes, but it’s important to remember that any thunderstorm has the potential to produce a tornado; some are just more likely than others.

Things clear up a bit for Friday (although a few hit and miss storms are possible through the Red River Valley) before another system pushes in for the weekend and we’ll see more significant chances for thunderstorms return.